Lake whitefish or dikameg is a species native to the Great Lakes and has been culturally important to the people of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON) since time immemorial. But in recent years, fish harvesters from the SON who rely on dikameg as a source of food and income, noticed a change in populations in Lake Huron.

Ryan Lauzon is a fisheries biologist with the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nations Fisheries Assessment Program and has been in conversation with the community about this change. A large factor, he believes, is the presence of invasive quagga mussels filtering nutrients out of the water.

“There really isn’t a lot of food left for the larval lake whitefish to eat, so the theory is that they’re basically starving to death and there’s no new fish able to enter the fishery,” said Lauzon also citing recreational fish stocking, climate change, and shoreline development as possible strains on whitefish. “There are just so many things going on that we believe are having a negative effect on the fishery.”

In 2021, Lauzon, along with Researchers Mary-Claire Buell, Kathleen Ryan, and Alexander Duncan received a Smart Great Lakes mini-grant from GLOS, enabling them to launch the Bima’azh project in order to help answer some of the community’s questions.

Bima’azh, an Anishinaabemowin word, can mean to track or follow along. And instead of relying only on western science or Indigenous knowledge, the project architects applied a two-eyed seeing approach to better understand the dikameg. Two-eyed seeing is a term coined by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall, and, when pertaining to research, recognizes and equally values Indigenous knowledge and western science.

“GLOS appreciates the effort to better understand and manage the lake whitefish population from various viewpoints. No one entity ever has all the answers. This is why the Bima’azh project is a Smart Great Lakes project,” said Katie Rousseau, Smart Great Lakes Liaison.

Over the past year, the team worked to:

- Understand concerns and observations of dikameg behavior by working with members of the SON, interviewing knowledge holders, and utilizing insights from existing interviews.

- Collaboratively design a fish-tracking telemetry array on an important shoal where the fish spawn.

- Hire local fish harvesters to catch fish for tagging and to help install the telemetry equipment on the lakebed.

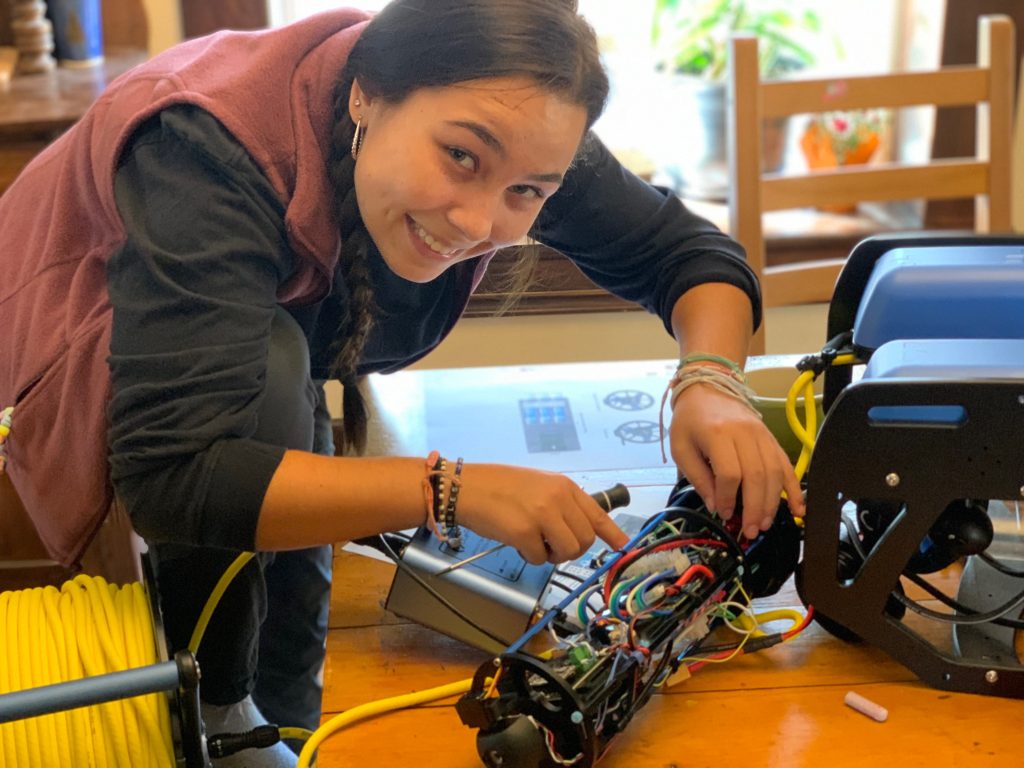

- Build a remotely-operated underwater vehicle (ROV) to visually inspect lakebed spawning areas.

- Analyze the data, in combination with Indigenous knowledge.

- Provide insights to the fish harvesters and the local community.

This approach meant collaborating with the community on details like the design of the telemetry moorings so that they could be fully removable, instead of leaving cinderblock anchors behind, as is typical for this type of system, says Buell, who leads Collective Environmental, a research and consulting company.

It also meant seeing the insights from the community as on equal footing with data collected, rather than viewing data as “validating” or “confirming” those insights. The result? The team is working toward a fuller understanding of changes in fish populations that will provide insights to those personally affected within the community.

Over the past year the team successfully collected the first round of data from the telemetry array and has begun exploring the spawning shoals using the ROV. Though they are still early in the process of analyzing the data, the team is already seeing trends in how fish interact with the shoal.

“Almost everything we’re seeing is lining up with what the fish harvesters told us we were going to see,” said Ruth Duncan, an intern with Collective Environmental and a member of the SON, “which is really cool.”

This particular telemetry array allows the team to triangulate a fish’s exact location and watch it move around the shoal during critical points in its lifecycle. And Lauzon says that they noticed something a bit strange in this data.

“We do know that some of those fish disappeared off that array after spawning and did not come back until the next spawning period,” he said. “Some left, and some fish seemed to kind of stick around.”

The more this team can discern from this data, the closer the fishery managers can come to pinpointing issues that may be affecting the wellbeing of the dikameg.

According to Buell, this kind of co-designed research project has to have community involvement at its core, from the very beginning.

“I think a lot of the successes so far have come from the community being granted the funds directly and having access to researchers who support these projects at the direction of the community, as opposed to, researchers saying ‘Here’s what we want to do. Hey, do you want to join us?’ In that scenario, communities are often having to conform to how the researcher operates,” said Buell. “We’ve completely flipped that script because the whole application was shaped by questions that arose from previous interviews with community members that had been done to say, ‘How do we answer these questions? Let’s find the money to do that.’”

Project partners include:

Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation Fisheries Assessment Program

Environment Office of Saugeen Ojibway Nation

Saugeen Fisheries Assessment Program

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Great Lakes Acoustic Telemetry Observation System

Watch the interview: