Getting real-time measurements of water conditions in the Great Lakes during the winter has always been a challenge for researchers.

In the Great Lakes, the winter is not just cold, but also punctuated with fierce storms that bring dangerous waves and strong winds. But most of all, leaving equipment out during the cold months is especially challenging due to ice that can form quickly, move, and crush expensive scientific equipment.

The danger, paired with limited funding, means that very little data is collected during a long period of time, usually December through March or April. This is especially true for real-time data, leaving scientists with a limited understanding of what’s going on in the lakes during this period.

“Great Lakes environmental monitoring data is scarce during the winter months,” said Ana Sirviente, Chief Technology Officer at GLOS. “This hinders our ability to understand lake processes, forecast them, and assess how climate change is impacting them.”

But in recent years, the monitoring community has begun ramping up efforts to expand monitoring capacities by developing and adapting technologies to withstand the extreme conditions and collect data, and even send it in real-time.

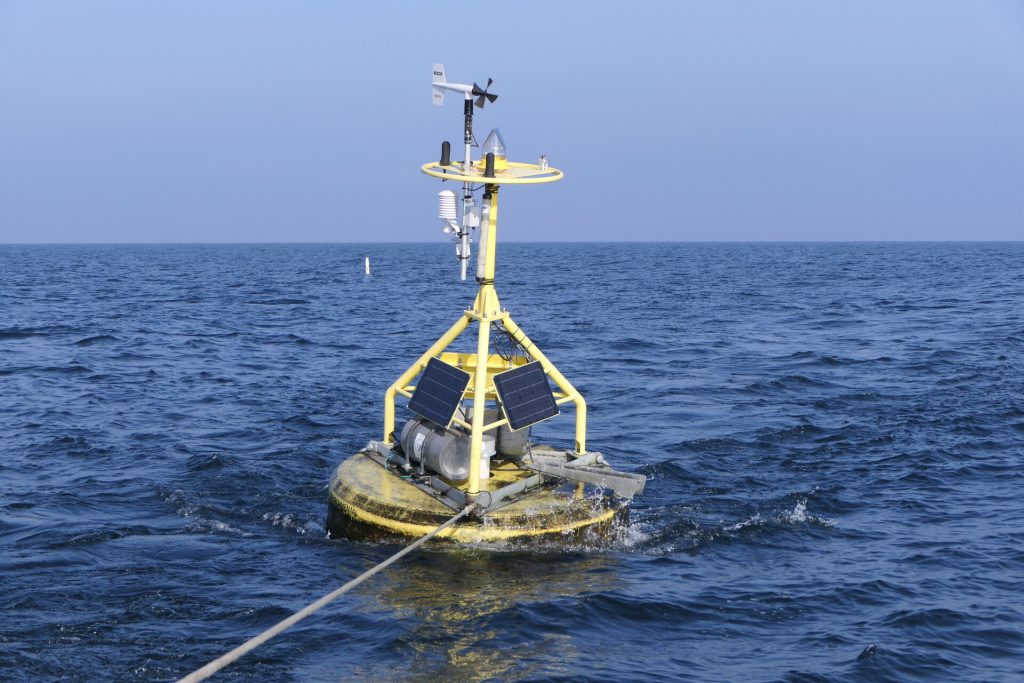

Every year, the Upstate Freshwater Institute (UFI) team, located in Syracuse, NY, pulls the Sodus Point, Oak Orchard, and Oswego Buoys out of Lake Ontario for the winter, and as the buoys power down, so does data collection in that area. But years prior, Dave O’Donnell, an engineer at UFI, had helped to build an over-winter system to measure real-time turbidity in an icy reservoir near New York City. The project had been an overall success and testing it in Lake Ontario seemed a logical next step.

“In Lake Ontario, surface conditions are much worse,” O’Donnell said. “We were trying to figure out, ‘Could we build a system that could survive the conditions.’”

Instead of three-foot waves in the reservoir, the Oswego site routinely sees winter waves over 15 feet. And with the possibility of pieces of ice sliding along those waves meant that this system would have to be extremely tough.

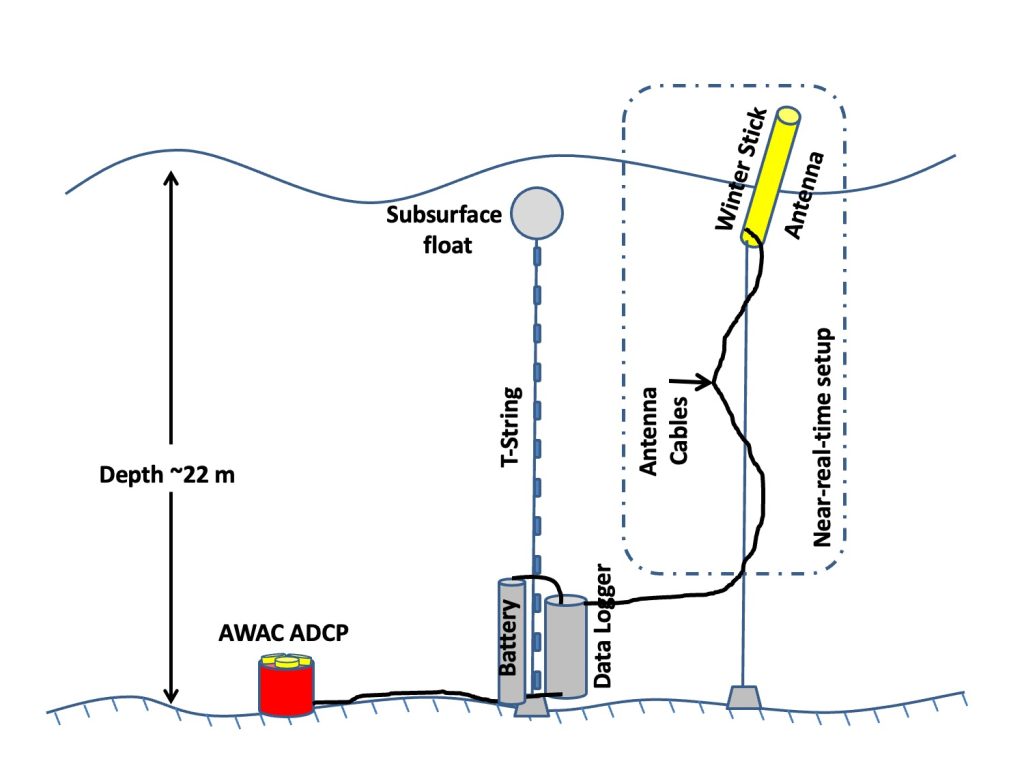

So O’Donnell and his team got to work. With funding support from a GLOS Smart Great Lakes mini-grant, the UFI team designed and built one overwinter monitoring system capable of transmitting data in near-real time. It features a durable float made of a modified “winter stick” enclosed in a PVC pipe that houses the antenna, and is attached, via a long cable, to a massive battery on the lake floor. The battery is capable of powering the data logger, sensors, and other equipment all winter, thanks to its 75 D cell batteries.

The Oswego system is equipped with:

- An acoustic wave and current profiler.

- A thermistor string, made of multiple temperature sensors positioned at varying depths in the water column.

- An antenna that runs from the bottom of the lake, up the float.

- A 4G modem and a data logger to transmit data.

Using mini-grant funds, the UFI team also deployed a mooring system at Sodus Point that collects the same parameters as the Oswego system. However, the Sodus system does not transmit data in real time and instead saves it until the UFI team can recover it in the spring and download it. These types of winter platforms are more commonly deployed in the Great Lakes.

This past November, after recovering their buoys, the UFI team headed out into the lake, sent the systems over the side of the boat and, with the help of a diver, configured them on the lakebed.

And then data began to flow from the Oswego system, and for the past several months, things have been running well, O’Donnell says. Data is currently flowing a few times each day to UFI from the Oswego system, and wave and temperature data is available on Seagull.

“What Dave and his team are doing is a great use of existing equipment – putting it to work in the off-season. It provides a nice snapshot of that part of Lake Ontario that we wouldn’t otherwise have,” said Shelby Brunner, Observing Technology Manager at GLOS.

During the field season the National Weather Service (NWS) in Buffalo regularly uses the nearshore data collected by the Lake Ontario buoys. During the winter the only observing platforms that provide data, meteorological data, are onshore.

“Having wave data in the winter is really game changing,” said Jason Alumbaugh, Lead Meteorologist and Marine Program Manager with NOAA-National Weather Service. “Any real-time wave guidance to compare against our wave model, which runs year-round, is a great asset to have.”

Following an agreement with the U.S. Coast Guard, NWS provides Small Craft Advisories through the winter season. The data provided by the overwinter Oswego system could help support this work.

More winter observations are needed in the Great Lakes and the region is working diligently to make that a reality.